The last tine on either end can be scaled slightly in your slicer to get a good fit. There should be some resistance so the tines slide easily, but not freely once the pieces are broken in.

I’m not sure why, I would do this step while it’s disassembled.)įirst, check that the 32 printed tines fit in the body snuggly with some resistance. Having established the holes, the piece can be reassembled with the brass strips and printed rails. Working from the middle out, you can achieve a tight and flat velostat sheet. Flip it around and pull the sheet tight, repeating this on the other side.

Screw an M3 screw down slightly to hold it in place. Once the sheet is sized right, place it in the bottom body and punch through into the middle hole on one side. Try fitting the doubled-up sheet in the bottom body part, trim off excess as needed. You want extra material on each side so you can stretch it taut. The 180mm isn’t crucial, the sheet is to be folded in half. It’s a good idea to solder the wire onto each of these now before they are in contact with the velostat, as the thin sheet is heat sensitive.Ĭut a sheet of velostat 96mm x 180mm. The extra brass is bent up to act as a connection point. Tape the printed part and the strip together, aligned at one end. Next, cut two brass strips ~4mm longer than the printed rail with holes in it. There’s tolerance built into the model but it’s unlikely that it will be too loose. If it’s too tight, try sanding or adjust print settings and try again. Now that the body pieces are printed, check that the dovetail joint fits snugly. The points are plotted at intervals of 3mm(the width of each tine) on the x-axis, and then a nurbs curve is drawn through them. In the grasshopper sketch, the tool is calibrated by reading the upper and lower reading limits and remapping them to 0-72mm, which is the range of the gauge. Here’s an instructable I referenced for the multiplexers by pmdwayhk: (Also used this for the base program) These pins connect to the arduino via two 16 channel multiplexers. We put 5v across it, and each tine will read voltage at a given point between 0-5v. The plastic is clamped on each end of the housing with a conductive strip, so the resistance values are nearly the same along one axis, and vary along the other.

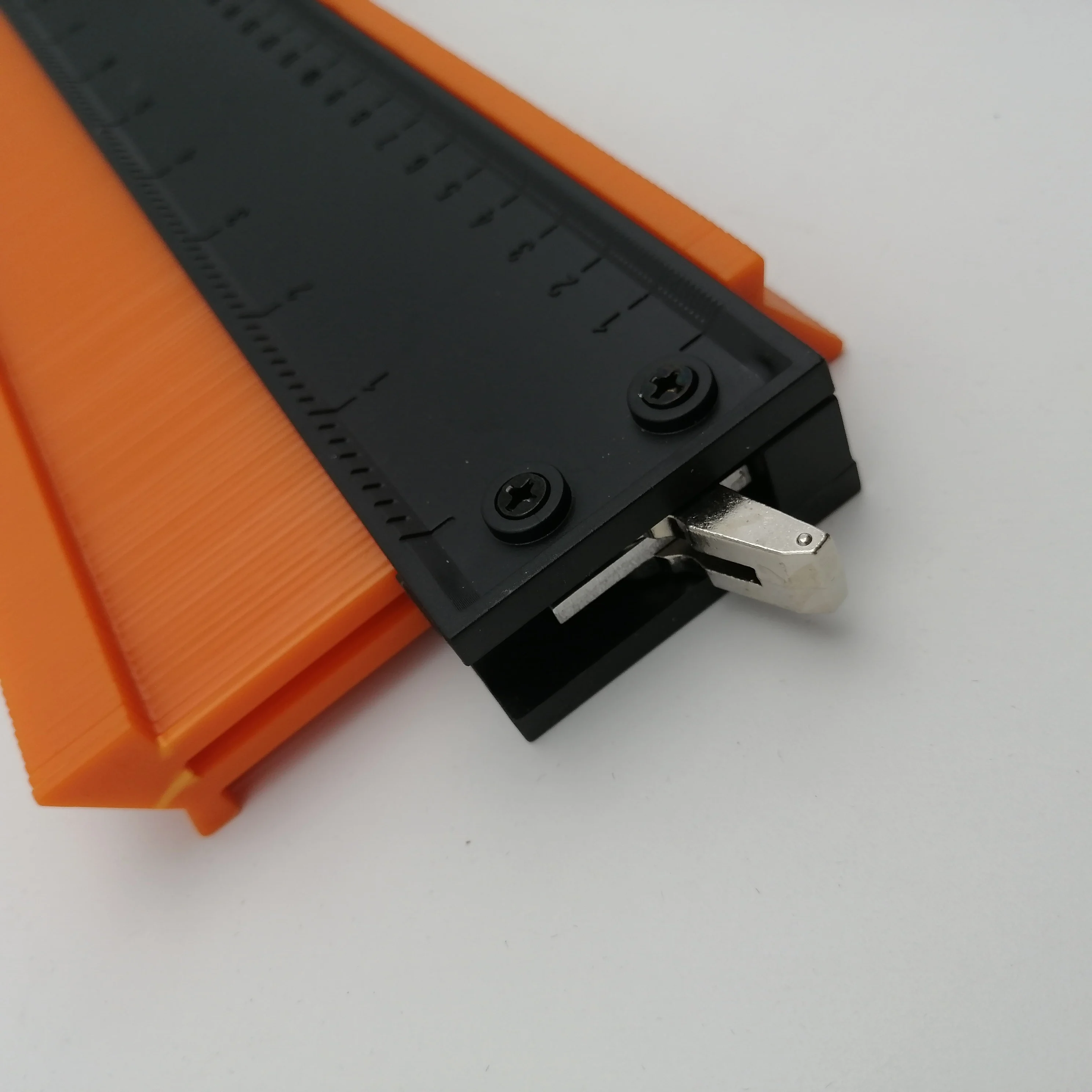

The same principle is at work here, except reoriented and multiplied.Īlso, the dovetail design is inspired by Tomalinski’s gauge: Here is a great instructable by lonelysoulsurfer that uses the velostat for a ribbon controller: This project illustrates the idea very well. The potentiometer is made from Velostat, an inexpensive conductive plastic sheet. The typical gauge also incorporates a metric and an imperial ruler, with some having inches and millimeters marked on both sides.Įdge magnets are included and these help to keep the gauge in place when profiling metal surfaces.At the heart of this tool is essentially a single linear potentiometer, with each tine of the gauge collecting an independent reading. This type comes with varying lengths of detachable extension modules or can be combined with other compatible adjustable models. The gauge may be fixed for smaller objects or adjustable when larger surfaces need to be profiled. Depending on the application, plastic pins may be are used for sensitive objects while steel pins are used for less sensitive surfaces. The typical contour gauge is made of heavy-duty metal or durable and lightweight polyethylene. When the contour gauge is pressed against the object, the pins conform to the shape of the object and the profile of the object can then be copied onto another surface or drawn.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)